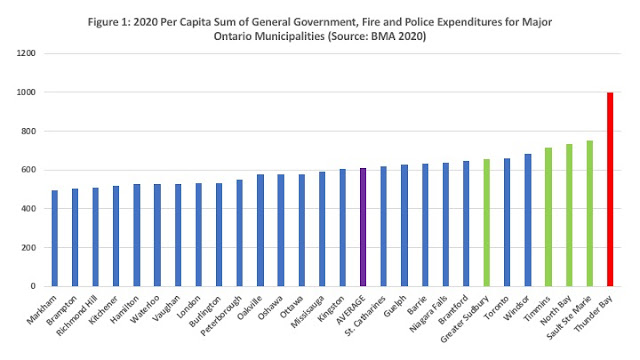

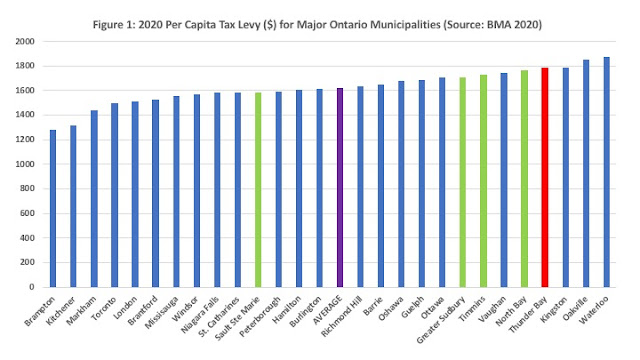

Thunder Bay spends one of the highest per capita amounts of major Ontario cities. Moreover, it has chosen to prioritize three things: general government, police, and fire services. Indeed, of 27 major Ontario municipalities, Thunder Bay spends the most per capita of its tax levy supported operating budget on these three things as illustrated in Figure 1. Indeed, nearly 60 percent of Thunder Bay’s operating tax levy is spent on these three items. Naturally, what it also implies is that there is less to spend on everything else and in fact, while Thunder Bay spends one of the highest amounts per capita and the most on general government, police and fire, it actually spends a lot less on everything else compared to these other cities.

Now, if I were a Thunder Bay city administrator tasked with addressing the above statements in response to a query by a municipal councillor, I would naturally respond by saying that yes indeed, councillor, the numbers are higher but they really do not tell the entire story because in Thunder Bay ‘general government’ is a broader and more encompassing term of innumerable complexities compared to other municipalities that are located in more densely populated and less policy challenged parts of the province. As well, I might even venture that perhaps Thunder Bay includes costs in general government that other cities do not as part of its own diverse and unique circumstances reflecting its special position as a northern municipality with serious social and economic issues of the utmost seriousness that in the fullness of time must be very seriously addressed.

Of course, that begs the question as to why the composition of the numbers that have been used in the above comparisons - which come from the BMA Municipal Report – would be so different given that they are supposed to be constructed and provided to allow for some type of standardized comparisons? Needless to say, at this point as a City Administrator I would probably respectfully argue that these are complex questions beyond the pale of the councillor's valuable time given their plethora of pressing duties and ultimately requiring further study by knowledgeable and qualified individuals with intimate knowledge of local realities. If pressed for details on the composition of general government spending in Thunder Bay, I would certainly take the request into consideration and get back at some future date as providing the data requires substantial resource expenditures given its all-encompassing complexity.

So, we are left to our own devices. In addressing the higher costs of certain municipal expenditures in Thunder Bay, perhaps we can focus on something more specific and better defined rather than something as amorphous as ‘general government’. Why not policing or fire? Figure 2 provides a first ranking of policing by presenting the number of police officers per 100,000 population obtained from Statistics Canada for 15 major Ontario centres in 2019 (with Hamilton only available up to 2017). It turns out that Thunder Bay does not have the highest numbers of officers per capita of these 15 cities. It is tied with Windsor at about 205 officers per capita.

No doubt there are extenuating circumstances as to why Windsor has so many officers. -perhaps there is more crime in border cities with a lot of casinos. Thunder Bay is a border city – well almost – but it is very close to the border. And we have a casino too. Lo and behold, Thunder Bay, also has a lot of crime so we must be like Windsor after all. And as for Ottawa which has so many fewer officers, it is the seat of government and also has innumerable other security forces such as our military and the RCMP which allow the municipality to spend less on policing. If only Thunder Bay could be blessed with a Canadian Forces base or perhaps a branch office of CSIS, we would be a more secure place. Moreover, Ottawa is inhabited largely by peaceful civil servants and government sector workers so it must be a more law-abiding town, right? But wait, Thunder Bay has over 30 percent of its employment in the broader public sector – not as high as Ottawa but still very high by provincial standards - so why no spillover into crime statistics?

Of course, the number of officers may be correlated with cost but perhaps policing resources in Thunder Bay are abundant because we pay officers less and therefore, we are getting more bang for our buck? Well, Figure 3 looks at the cost of policing for these same 15 major Ontario centres using cost measures from the BMA 2020 Municipal Report. The cost measure is what is available – the cost of policing in terms of dollars spent on policing per $100,000 of tax assessment. Using this measure, Thunder Bay comes in third place – behind Windsor and Timmins – at $439 per $100,000 of taxable assessment. Put another way, in Thunder Bay, if you have a $250,000 home, you are probably paying close to $4,000 in property taxes on that home. Of that amount, $1098 (2.5 times 439) is going to pay your share of police services – about 28 percent of your taxes. In other words, in Thunder Bay, one-quarter of the tax levy goes to provide policing services. A good question is how this might compare to other cities but good luck conveniently getting the data for that.

Are there good reasons why we spend a lot on policing in Thunder Bay. Yes, councillor, maybe. Or, maybe not. However, relying on the City of Thunder Bay to make the case rather than a more impartial source probably results in a predetermined answer. It still does not change the fact that we are at the top of the list both in terms of policing numbers per capita and in costs as measured by the publicly available data. Does that mean we need do nothing about it? No. We can always do better. That does not mean spending more on policing, it means finding ways to achieve current outcomes with less money.